Istituto Svizzero invites Fellows and Senior Fellows to connect with the public during their time in Rome, Milan, or Palermo, offering a unique glimpse into the evolution of their practice and research. Through a series of questions, the public gain insights into the Fellows’ ideas, projects, and works.

Angela Gigliotti is an architect and academic. She is affiliated with ETH Zürich / gta, where she is conducting research in the field of architectural history. Her current project focuses on a monographic thesis titled The Ticinification of Italy (TI–IT): Construction, Financing, and Promotion of Swiss Proximal Coloniality from Ticino to the Kingdom of Italy (1857-1947). She holds an MA in Architecture from the Politecnico di Milano and a PhD in Architecture from the Aarhus School of Architecture. In Rome, she will carry out a case study on the architectural, economic, and social history of the construction of Villa Maraini, as a significant example of intercultural and transnational Italo-Swiss architecture.

What is the main project you will be working on during your residency?

At Istituto Svizzero, I aim to kick off my habilitation research project titled “The Italian Ticinification: Building, Financing, and Promoting Swiss Proximal Coloniality from Ticino to the Kingdom of Italy (1857-1947).” In brief, with my background in the history of practices, labor, and production studies, I aim to study the impact that some Ticinese actors had on the Italian built environment by reinvesting the capital derived from various extractive capitalist operations. During this first semester of study in Rome, I will focus primarily on a pars pro toto case study: the construction of Villa Maraini, a transnational architecture whose historiography still lacks a labor perspective that I aim to contribute to.

Pars Pro Toto

What do you expect from the residency?

I expect to be able to access two sets of materials: on one side, the building as an artifact; on the other, the primary and secondary sources preserved at Istituto’s archive and library and at the Archivio Storico Capitolino. Specifically, I will look at three clusters: the construction of the Villa from the Ludovisi-Boncompagni ownership to the Maraini ownership; the maintenance of its premises throughout the years; and information related to the Maraini family and their real estate portfolio at large, as the family is one of the pivotal actors under study in my overall research project.

How do you think the dialogue between art and science can influence your work?

As an architectural historian, I have always nurtured my practical background as an architect. In 2015, I co-founded the research-based architectural practice OFFICE U67, which has offered me the possibility to use exhibition, set, and graphic designs as means to share the research findings from my academic career. Reaching the general public and breaking the walls of academic and disciplinary boundaries is the real essence of designing spatial installations by occupying a physical space to disseminate academic outcomes. Istituto Svizzero fuels and inspires my approach by offering many occasions for collaborating across art and science, both formally and informally. In my case, I am particularly interested in instances so far neglected by dominant and overlooked curatorial and scientific narratives, such as class, labor, gender, and race.

What influences your work?

My work is influenced by the contemporary conditions in which I am working. As an architect, educator, and researcher, I have worked in transnational settings, contexts, and environments where physical and national boundaries are often crossed, blurred, and overlapped, and the travel component is very pivotal. As such, I am constantly attracted to an ongoing discourse at the global scale, rather than the local one, in the disciplinary contents under study as well as in my methodology.

Who do you admire most in history?

More than who, I think it is the what that I admire most in dealing with the history of architecture. After completing a PhD where a significant component was related to contemporary labor conditions in architecture under neoliberalism and having dealt with qualitative data collection through interviews, I have been highly exposed to how architects implicitly or explicitly promote their projects as commodities, leaving aside the work conditions in which they operate. I have learned to appreciate the silenced actors rather than the loud ones. By prioritizing quantitative data collection, big data analysis, distant reading, and the act of giving voices to actors and instances that have been muted and unheard for too long.

What music are you currently listening to?

I am a very curious person. Looking at my phone, one might find a range from classical music, such as orchestra and ballet, to trap and electronic music. My guilty pleasure, especially when traveling late at night, is to listen to the same radio shows I have been following since high school, broadcasted on Italian Radio Deejay. Somehow, despite a life in transit, listening to the same shows and radio voices allows me to understand current trends in music and decide whether to download a song on the spot, while also making me feel at home.

Life in transit

Do you have any rituals/routine during work?

I am a to-do list person; I always have been. So, I check calendars, notes, and emails often, from when I wake up in bed to when I go to bed. The ritual of marking things as checked off my to-do list always gives me a high sense of satisfaction.

To-Do-List

What legacy do you hope your research will leave behind?

I hope to contribute to writing an alternative historiography about the impact of Ticinese actors on the Italian built environment. One that might expand the single-male heroic narrative promoted for too long and its current periodization in architectural history, which has so far been limited to early modernity and a few “masters.” One that aims to problematize and unravel colonial instances, extractivist dynamics, and labor perspectives. One that might unlock how the capital extracted from farming and plantation activities has shaped the built environment in contexts much farther from the extraction sites.

What fascinates you about Rome?

The sunset and the horizon seen from the highest point in the top tower of the Istituto fascinate me the most.

Sunset at Istituto Svizzero

The future for you is…?

Now.

Maria Silvia D’Avolio (1985) è una ricercatrice post-dottorato in architettura, sociologia e studi di genere. Ha conseguito un dottorato di ricerca in Sociologia presso l’Università del Sussex. Ha lavorato come ricercatrice in diverse università internazionali, tra cui l’Università di Scienze Applicate di Zurigo, il King’s College di Londra e l’Università di Portsmouth. Tra il 2016 e il 2022 ha insegnato sociologia, criminologia e studi di genere nel Regno Unito presso l’Università del Sussex e l’Università di Brighton. A Roma, ha lavorato a un progetto che esplora il ruolo di alcune architette e urbaniste socialiste/comuniste e femministe tra gli anni ’60 e ’80. Il progetto ha esaminato in che modo le loro convinzioni politiche abbiano influenzato i loro progetti architettonici e il loro pensiero teorico.

A quale progetto lavorerai durante la residenza?

Il progetto intende investigare la figura professionale di alcune architette socialiste e comuniste, e parallelamente o contestualmente femministe, che hanno operato a Roma tra gli anni ’60 e ‘80 e analizzare l’impatto delle loro convinzioni politiche sulla loro pratica architettonica e sul proprio pensiero teorico. L’intento è di andare oltre la presentazione di resoconti biografici, inquadrando l’attività di queste architette nel contesto politico e architettonico dell’epoca e mettendo in luce le loro reti professionali nel più vasto ambito dell’industria delle costruzioni. Le carriere professionali delle architette identificate nel progetto vengono discusse sulla base dell’analisi di materiale primario e secondario raccolto tramite una varietà di metodi di ricerca qualitativi, tra cui l’analisi di materiale d’archivio e interviste ad alcune protagoniste dell’architettura di quel periodo.

Quali sono le tue aspettative per questa residenza?

La possibilità di avere il tempo e il supporto necessari per portare avanti il mio progetto. Inoltre, il mio percorso di formazione, tra architettura, sociologia e studi di genere, è caratterizzato da una forte interdisciplinarità, per cui avere la possibilità di discutere i temi di mio interesse con altre persone provenienti da vari ambiti disciplinari è un elemento essenziale per lo sviluppo del mio progetto. Il fatto di vivere a stretto contatto con i fellows, caratterizzati da background e formazione in discipline molto varie, si sta rivelando una preziosa fonte di idee e riflessioni.

E poi mi aspetto di passare molte ore a leggere in giardino.

Questo verde è un ottimo contrasto con le pagine di un libro.

Come pensi che il dialogo tra arte e scienza possa influenzare il tuo lavoro?

Il mio lavoro è molto legato allo studio di movimenti storici di attivismo dal basso che hanno sempre avuto la necessità di utilizzare forme DIY di espressione e azione. La mia ricerca entra continuamente in relazione con metodi performativi ed espressivi come la musica popolare, la fotografia, la produzione di ciclostilati e volantini. È utile comprendere come le tecniche e le pratiche artistiche siano state utilizzate in passato e come possano essere adattate alle azioni di attivismo contemporanee.

Cosa influenza il tuo lavoro?

I temi della giustizia sociale, della solidarietà e dell’azione collettiva ricoprono un aspetto fondamentale della mia vita, diventando un elemento fondante anche del mio lavoro.

Chi ammiri di più nella storia?

La mia pratica politica si basa molto sull’aspetto comunitario della vita sociale, motivo per cui sono molto scettica nei confronti della celebrazione individuale. Tuttavia, sono affascinata da alcuni momenti storici localmente diffusi e non legati a date precise, come l’occupazione universitaria alla fine degli anni ‘60, le lotte partigiane o il contesto che ha caratterizzato i circoli femministi degli anni ‘70.

Che musica stai ascoltando attualmente?

Sono una di quelle persone noiose e abitudinarie che continuano ad ascoltare per il 90% del tempo la stessa musica che ascoltano da sempre. Nonostante ciò, sono molto entusiasta del 10% che, grazie al passaparola di amici fidati o all’algoritmo di Spotify, introduco costantemente ma lentamente nel cuore delle mie playlist. Sono convinta che sia una conseguenza inevitabile del fatto di essere stata adolescente durante il periodo dei lettori mp3 che contenevano solo una manciata di album.

Hai qualche rituale/routine durante il lavoro?

Per il tipo di ricerca che conduco ho la necessità di consultare archivi e incontrare persone con cui parlare e confrontarmi, e questo non mi permette di avere una routine quotidiana fissa. Soprattutto considerando gli imprevisti, come l’Archivio Centrale dello Stato che ho trovato chiuso per restauro proprio durante la mia permanenza a Roma.

Resta ferma per un turno e pesca dal mazzo degli imprevisti: fondo non consultabile.

Cosa ti affascina di Roma?

È una città bellissima e molto dinamica: eventi, associazioni, lotte e solidarietà si trovano ovunque. Tutto questo avviene tra i monumenti romani, sui sampietrini, e tra il vociare delle persone per strada. Per esempio, è stato incredibile passare davanti al Circo Massimo o al Colosseo circondata da cartelli, slogan e canti durante la manifestazione del 25 novembre, tra il fumo dei fumogeni viola di Non Una Di Meno.

25 novembre, giornata internazionale contro la violenza sulle donne. Immagine presa da una story pubblicata sulla pagina di Non Una Di Meno Roma.

Il futuro per te è…

Preoccupante. Mi spaventano sia la deriva che la politica e la crisi ambientale stanno prendendo che la reazione passiva che abbiamo assunto nei loro confronti come società.

Luca Piccoli (1996) è architetto e dottorando SNSF in museologia presso l’Università della Svizzera Italiana, in co-tutela con l’Università Sapienza di Roma. Le sue ricerche esplorano la fondazione dei primi musei pubblici di Roma attraverso gli occhi e le esperienze di coloro coinvolti nella progettazione degli spazi espositivi. Ha conseguito il master presso l’Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio e ha completato la sua formazione con un’esperienza professionale a Parigi nel campo dell’urbanistica e della progettazione di spazi pubblici (Obras architectes, TVK). A Roma porterà avanti la ricerca sulle origini e lo sviluppo dei musei della città durante il Grand Tour europeo, focalizzandosi sul ruolo degli addetti alla configurazione degli spazi espositivi e sull’influenza del pubblico nelle scelte di allestimento.

A quale progetto lavorerai durante la residenza?

Lavorerò sulla mia tesi di dottorato afferente al progetto Visibility Reclaimed. Experiencing Rome’s First Public Museums (1733-1870). An Analysis of Public Audiences in a Transnational Perspective (progetto FNS 100016_212922) diretto dalla Professoressa Carla Mazzarelli presso l’Università della Svizzera italiana, in co-tutela con la professoressa Chiara Piva della Sapienza Università di Roma. Nello specifico, i miei studi esplorano le origini della Museografia nella Roma del Settecento, letta dal punto di vista delle pratiche esperienziali dei primi pubblici: come i comportamenti e le richieste dei visitatori hanno contribuito a dare forma agli spazi espositivi, nonché il ruolo delle istituzioni nel disciplinare ed influenzare lo sguardo del pubblico stesso. Superando paradigmi “nazionali”, particolare attenzione è posta sulla mobilità dei visitatori dei musei, sulle loro provenienze e categorie sociali, con un focus sul pubblico di architetti: il dialogo di questi con le istituzioni e la diffusione dei modelli museografici tra l’Italia (Roma nello specifico) e il resto d’Europa.

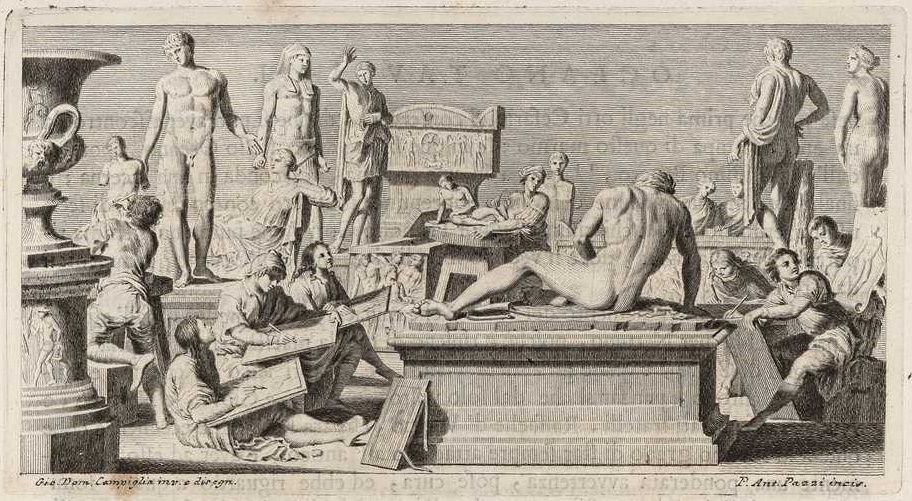

Pietro Antonio Pazzi da un disegno di Giovanni Domenico Campiglia, Seduta di disegno in una sala del Museo Capitolino, da Bottari 1741-1755, vol. III, p.1.

Quali sono le tue aspettative per questa residenza?

Avere la possibilità di studiare liberamente negli archivi e nelle biblioteche della città, dove si conservano testimonianze e richieste di copia e di accesso ai primi musei (Archivio Storico Capitolino, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Archivio Apostolico Vaticano, e altri). Oltre a ciò, spero di avere modo di ampliare lo sguardo oltre ai temi e cronologie di ricerca: la principale motivazione alla base della mia candidatura è stata la prospettiva di confronto con altri ricercatori e artisti. Mi aspetto quindi, prima di tutto, visite e dialoghi.

Come pensi che il dialogo tra arte e scienza possa influenzare il tuo lavoro?

Prima di iniziare questa residenza, scontatamente, avrei affermato che il dialogo con i residenti artisti sarebbe stato incentrato sul ruolo dei musei contemporanei: come loro si avvicinano da un lato alle istituzioni, dall’altro al pubblico. Dopo due mesi, posso dire che si tratta di uno scambio molto più proficuo: tutti abbiamo interessi, interrogativi e ricerche differenti, ciascuna con punti di contatto. Ho sempre percepito la pratica artistica come parallela e complementare alla ricerca accademica: pur usando strumenti diversi, alimentiamo riflessioni affini.

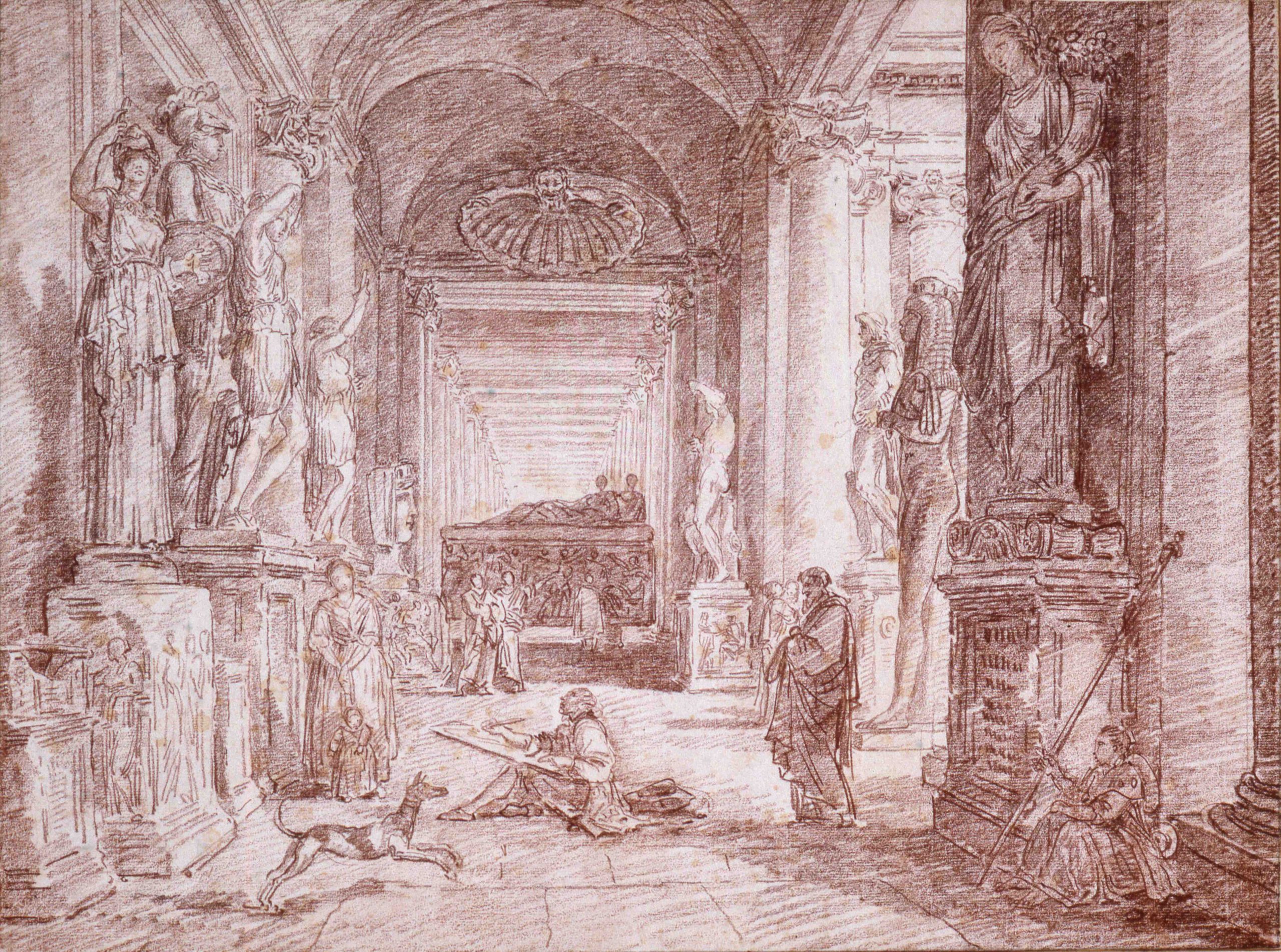

Anonimo, Bernardino Nocchi (?), La Scala Simonetti, tempera, Musei Vaticani.

Cosa influenza il tuo lavoro?

Provenendo da una formazione in architettura e urbanistica, penso di poter affermare che il mio lavoro è prima di tutto influenzato dall’osservazione diretta dei luoghi che studio e della loro appropriazione. Sempre sullo stesso piano, sento di lasciarmi sempre ispirare dalle storie a cui cerco di espormi, possano provenire da libri, film o conversazioni.

Quale personaggio storico ammiri maggiormente?

Non saprei come rispondere a questa domanda: dipende sempre dai punti di vista. Credo sia lo stesso motivo per cui mi interesso alla museografia: la disposizione delle collezioni e la configurazione degli spazi espositivi definiscono sempre un modo di vedere (Svetlana Alpers, The Museum as a way of seeing, in Ivan Karp, Steven D. Lavine (a cura di), Exhibiting cultures, the poetics and politics of museum display, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, 1991).

Quale musica stai ascoltando ultimamente?

A costo di sembrare ossessionato dal Settecento, ultimamente ascolto spesso il Don Giovanni di Mozart: trovo ancora incredibile la sua capacità di divertire ed emozionare allo stesso tempo (in particolare il primo atto). In ogni caso, da quando sono arrivato a Roma sento l’esigenza di scoprire nuova musica.

Hai qualche rituale o routine lavorativa?

Prima di iniziare la giornata di lavoro, tendo a prendere in mano un libro qualsiasi: da romanzi a saggi, preferibilmente non pertinenti alle ricerche in corso. Per il resto, sto scoprendo una routine dettata dai tempi di Roma: dai tragitti per raggiungere gli archivi e le biblioteche (che avrei la tendenza a percorrere a piedi), all’opportunità di approfittare di un tempo così favorevole. Certo, mi sento davvero grato di poter adattare la mia routine a un luogo come Villa Maraini.

Qual è l’eredità che speri di lasciare attraverso la tua ricerca?

Collocandomi tra gli studi sulla storia dei primi musei di Roma e dei loro pubblici, nonché sull’embodied encouter dei visitatori con gli spazi espositivi, spero di contribuire a una nuova lettura dell’evoluzione di queste istituzioni. Studiare le origini del progetto architettonico dei primi musei intende riscoprire possibilità di avvicinamento alle opere oggi forse perduti o non del tutto considerati: lo scopo è di invitare a visitarli senza dare nulla per scontato, interrogandoci sul loro ruolo e riscoprendo sempre nuovi punti di vista sulle collezioni a noi pervenute.

Quali elementi ti affascinano della città di Roma?

Per rispondere a questa domanda, mi diverte riprendere un’espressione che ho letto di recente: “O bella Roma! E quanto tempo ho perduto girando gli altri paesi! Mi par di viaggiare ogni giorno, perché ogni giorno vedo cose nuove (…)” (Lettera di Scipione Maffei a Isotta Nogarola Pindemonti, Roma, 22 agosto 1739, in Celestino Garibotto (a cura di), Scipione Maffei. Epistolario (1700-1755), Vol. II, Milano, Dott. A. Giuffrè Editore, 1955, p. 890).

Credo di condividere questo sguardo: effettivamente Roma si sta rivelando una scoperta nel quotidiano. È senza dubbio un aspetto che vorrei esplorare nelle mie ricerche: la curiosità che spinge a viaggiare, le aspettative ed epifanie di coloro che giungevano a Roma nell’epoca del Grand Tour.

Hubert Robert, Le Dessinateur au Musée du Capitole, vers 1762-1763, Musée de Valence.

Il futuro per te è… ?

Direi imprevedibile. Nel personale, spero in futuro di affinare sempre di più, oltre alla concentrazione, uno spirito di adattabilità, lontano da abitudini. In questo senso, il programma transdisciplinare dell’Istituto si sta rivelando particolarmente benefico: negli scorsi due mesi sento di essere stato invitato continuamente a riflettere al di fuori del mio sistema di riferimenti.