Istituto Svizzero invites Fellows and Senior Fellows to connect with the public during their time in Rome, Milan, or Palermo, offering a unique glimpse into the evolution of their practice and research. Through a series of questions, the public gain insights into the Fellows‘ ideas, projects, and works.

Maria D. Rapicavoli (1976) è un’artista residente a New York. Assieme all’architetto e ricercatore Fabio Furiassi, ha sviluppato nell’ambito di Palermo Calling/Art & Science 2024 il progetto di ricerca Un teatro siciliano: l’aula bunker del carcere dell’Ucciardone di Palermo. Lo studio si propone di collegare e organizzare i dati frammentari sull’aula bunker e sul maxiprocesso alla mafia, i quali, a causa di calamità naturali e incuria archivistica, rischiano di andare perduti. In questo contesto, il progetto mira a esaminare criticamente e ricomporre artisticamente la storia dell’architettura del tribunale, in relazione alla sua storia politica, al fine di preservarne la memoria e renderla accessibile a un ampio pubblico.

A quale progetto lavorerai durante la residenza?

Inizialmente, la mia ricerca si concentrava esclusivamente sull’aula bunker del carcere Ucciardone di Palermo, sia come elemento architettonico che come simbolo della lotta alla mafia in Italia.

Tuttavia, questo periodo di residenza qui a Palermo, insieme agli incontri con persone che hanno vissuto quegli anni in prima persona, mi ha portata a spostare l’attenzione su ciò che l’aula rappresenta nella memoria storica e personale in un momento così traumatico della storia d’Italia e della Sicilia. Da siciliana, sento fortemente l’esigenza di raccontare l’antimafia, l’impegno e il sacrificio di giudici come Falcone e Borsellino, che hanno lottato con determinazione per sradicare la mafia, sia come mentalità che come associazione criminale. Il risultato della ricerca che sto portando avanti durante la residenza sarà un’opera installativa multimediale che spero di presentare inizialmente qui a Palermo e, in seguito, di portare all’estero.

Arch. Martuscelli che spiega il progetto dell’Aula Bunker

Dettaglio di un articolo del giornale L’ora

In che modo l’ambiente dell’Istituto Svizzero influenza la tua ricerca?

Il supporto professionale e l’ascolto attento alle mie esigenze sia di tipo logistico che personale sono stati di fondamentale importanza per lo sviluppo della mia ricerca in un contesto non sempre facile, anche alla luce delle tematiche delicate che sto portando avanti nella ricerca.

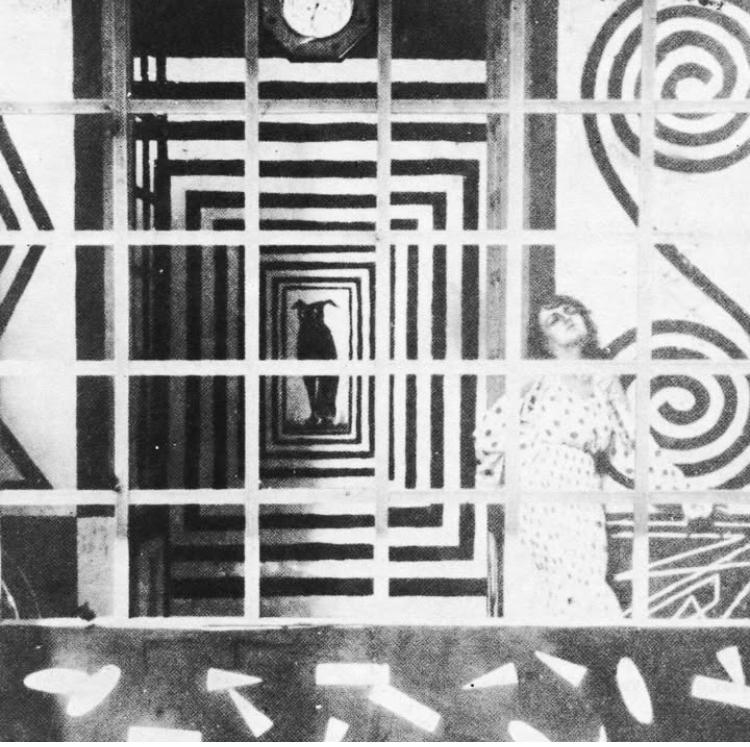

Research image

Qual è l’oggetto più strano che tieni nello spazio di lavoro?

Non so quanto siano strani, ma da quando sono arrivata a Palermo ho acquistato diverse piante: quattro succulente, un banano, una pianta di caffè e una di menta. Accanto alle piante tengo una cartolina d’epoca che ho trovato in una piccola libreria storica della città. La cartolina ritrae una donna elegante, con un ampio cappello piumato e un abito lungo in stile liberty, che sfreccia sui pattini a rotelle portando su un cuscino due volpi (vive o morte, non si capisce). Ho anche comprato una bicicletta usata nei colori rosa e nero (quelli della squadra di calcio del Palermo) e l’ho chiamata Rosy, che sta per Rosalia, la santa patrona di Palermo. La uso tantissimo e quando partirò la regalerò a chi verrà in residenza dopo di me.

Piante e cartoline

In che modo l’approccio transdisciplinare arricchisce la tua ricerca?

Mi consente di integrare prospettive diverse, offrendomi una visione d’insieme più completa e un pensiero critico più ampio, che sintetizzerò nella mia pratica artistica.

Research image

Cosa influenza il tuo lavoro?

Osservare i dettagli sociali e architettonici di Palermo. Andare in giro per i mercati di Palermo, dove la compravendita e gli scambi commerciali e umani si intersecano e danno una visione delle dinamiche sociali della città. Ho fotografato tantissimi oggetti in vendita a Ballarò e al mercato del Capo. Una meraviglia di colori, forme e memorie che difficilmente posso trovare a New York, città in cui vivo da diversi anni.

Dettagli al mercato di Piazza Marina

Hai qualche rituale/routine durante il lavoro?

Caffè, correre al lungomare, doccia calda, acqua alle piante e passeggiate in bicicletta.

Rosy

Che musica stai ascoltando attualmente?

Mina, Franco Battiato, De Andrè, gli Uzeda (gruppo rock storico siciliano) e la Ninna Nanna di Mozart

Hai un posto preferito a Palermo?

Piazza Bellini, di notte

Qual è la cosa più inaspettata che ti è capitata durante la residenza?

La facilità con cui si sono stabiliti i legami umani e artistici con altr* residenti, nonostante i diversi background e le diverse età. Mi sento fortunata, perché ognun* di loro ha delle qualità speciali che arricchisce il mio sapere e nutre il mio spirito.

Il futuro per te è… ?

Più progetti in Europa.

Research Image

Alexander Kamber is a doctoral researcher in the field of Cultural Analysis at the University of Zurich.

His SNSF research project (doc.ch) examines the relationship between moving bodies and their

environments in theatre and dance around 1900. By examining intersections between body practices

and the life sciences – medicine, psychology, and biology – his project situates early 20th-century body

culture within a history of ecological thought. He holds a master’s degree in Cultural Studies with a

specialization in Philosophy and History from Leuphana University of Lü neburg. In 2023, he was a

visiting researcher (Performance & Gender Studies) at mdw – University of Music and Performing Arts

Vienna. His current novel “Nachtblaue Blumen” was published by Limmat Verlag in 2024. In Rome, he

will examine the dance experiments of the early Italian Futurist movement with a particular focus on

their environmental knowledge.

What is the main project you will be working on during your residency?

I will work on my dissertation in cultural studies, which investigates how early 20th-century body culture (dance, theatre, gymnastics) intersected with life sciences (medicine, psychology, ecology) to shape new conceptions of the human body. While in Rome, I will research Italian Futurism’s experimental performances, which will contribute a chapter to this broader cultural history. While Futurism is traditionally interpreted as a purely machine-oriented art movement, my research reveals how these avant-garde artists combined mechanical and vitalistic elements – an understudied aspect that offers new perspectives on the movement. I’m particularly interested in medical and spiritualist influences, as well as critical and also feminist positions within and at the margins of the movement that challenge and subvert the classical image of Futurism as a homogeneous aesthetic program. My project takes an interdisciplinary approach: I’m fascinated by the intersections between performance and life sciences, such as the Italian Futurists‘ belief that theater and dance could train the audience’s nervous system – an idea that connects to contemporary medical discourses.

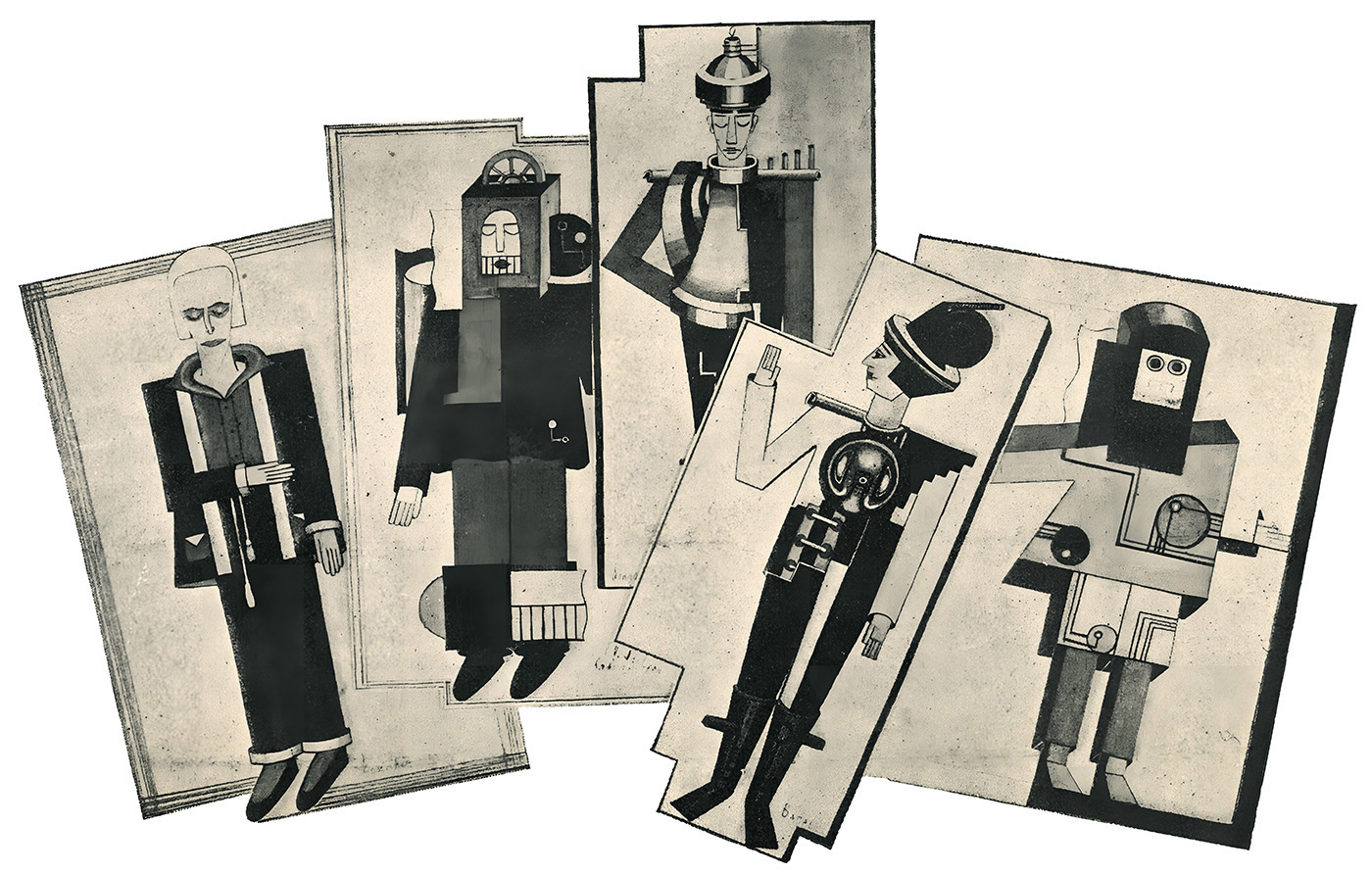

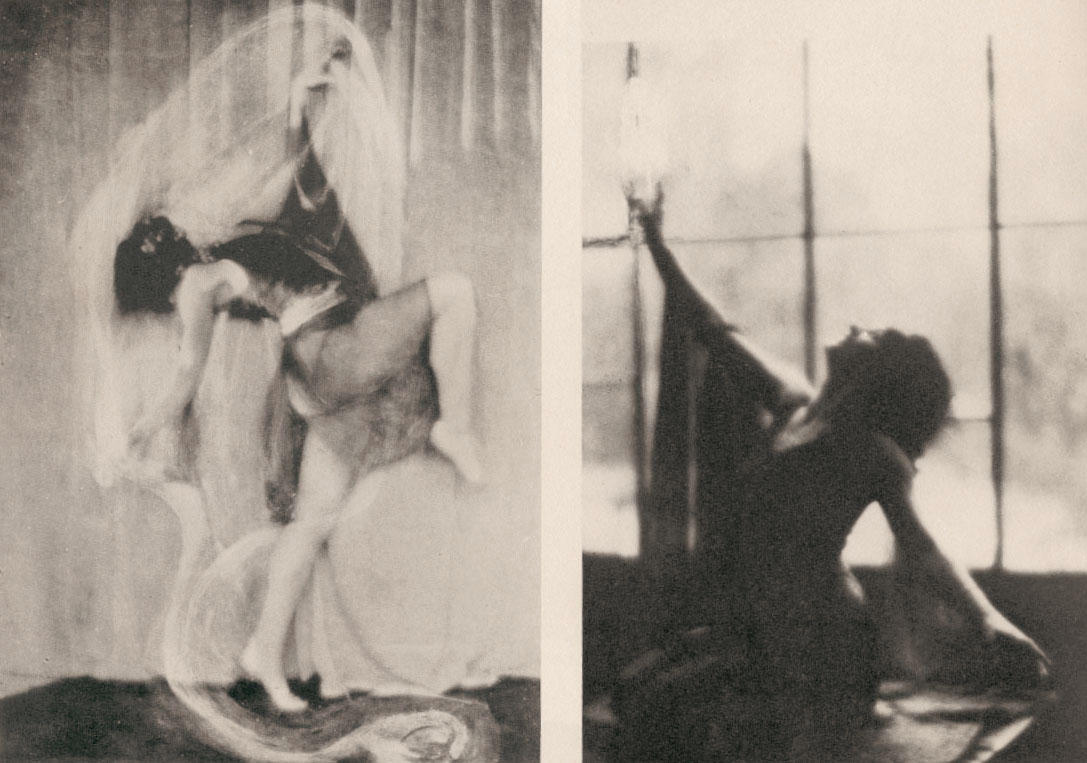

‘L’Angoscia delle macchine’ di Ruggero Vasari nelle scene e nei figurini di Vera Idelson, 1925.

Source: Adrien Sina Collection – Feminine Futures.

What do you expect from the residency?

Beyond the opportunity to conduct archival research on site, I look forward to exchanging ideas and collaborating with other researchers in Rome, as well as networking with fellow residents.

How do you think the dialogue between art and science can influence your work?

It plays a central role in my dissertation. I’m interested in how both spheres influence each other’s knowledge production, raise similar questions, and address related problems. I’m equally intrigued by the productive tensions that emerge between these fields, particularly when sciences attempt to approach subjective dimensions of experience and interpretation.

What influences your work?

I am particularly interested in historical perspectives that challenge disciplinary boundaries, revealing unexpected connections and productive tensions between seemingly unrelated fields of knowledge.

Who do you admire most in history?

There isn’t one single person I „admire most.“ However, when it comes to my current research project, an inspiring figure is the dancer Valentine de Saint-Point. She joined the Futurist movement, then challenged its misogyny with her Manifeste de la femme futuriste before breaking away from the movement and becoming an anti-colonial activist fighting European imperial dominance in Egypt and Syria. Also: Since entering university, I have consistently returned to Walter Benjamin’s work, appreciating his innovative and poetic approaches to historical analysis.

Photograph of Valentine de Saint-Point, 1913-14.

Source: Giovanni Dotoli Collection

What music are you currently listening to?

While I usually like to listen to 80s New Wave and Post-punk, being in Rome has rekindled my love for Italo Disco.

Do you have any rituals/routine during work?

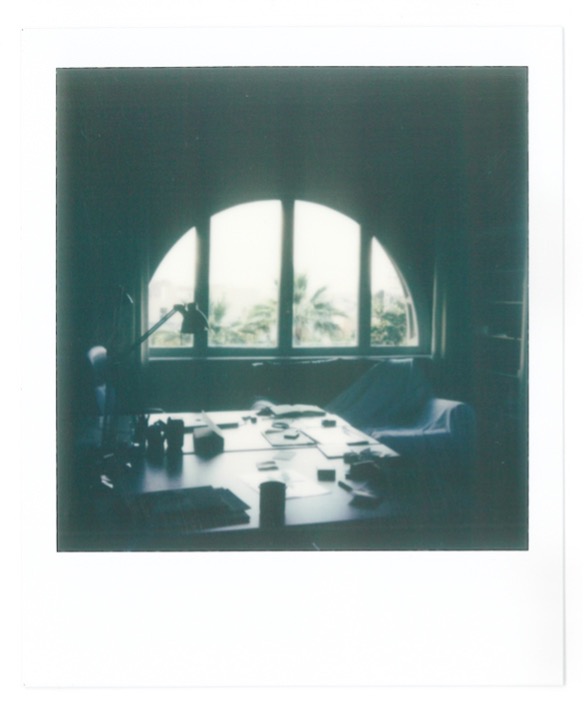

In Rome, I enjoy working in the quiet of the Istituto Svizzero library and meeting other fellows for coffee at the bar or on the terrace. In the afternoons, I love exploring the Quartiere Coppedè, a fantastical architectural blend of Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Baroque, and medieval elements. A late-night visit to Come il Latte gelateria is also a must.

What legacy do you hope your research will leave behind?

I hope to contribute engaging insights while creating connections and collaborative opportunities for other researchers working on similar topics.

What fascinates about the city?

How it embodies the tension between tradition and modernity on every street corner. I enjoy the city’s chaotic vibrancy and energy, and the (ridiculously) wonderful weather!

The future for you is… ?

I plan to continue my academic career, further exploring the dialogue between art and life sciences. Alongside my academic work, I will continue writing literature (my latest novel Nachtblaue Blumen was published in March 2024).

Source: YouTube

Domenico Singha Pedroli (1994) è un regista, artista e architetto con sede a Lugano, Parigi e Bangkok. Con un approccio multiculturale e multidisciplinare, le sue opere articolano narrazioni complesse che esplorano il tema delle tracce e dell’identità in tutta la loro mutevolezza. Formatosi in architettura all’USI e nelle arti visive a Le Fresnoy – Studio national ha sviluppato una sensibilità per la fotografia, il cinema, la videoarte e la VR. Il suo lavoro è stato recentemente esposto a Visions du Réel, Louvre-Lens, Bangkok, Pechino e Busan. A Roma svilupperà il progetto transdisciplinare Mythopoiesis che si propone di dare una lettura critica e contemporanea delle Metamorfosi di Ovidio, ampliando la riflessione sul potenziale della mitopoiesi come atto creativo, combinandolo con l’evoluzione dei luoghi dimenticati della città.

A quale progetto lavorerai durante la residenza?

Durante i dieci mesi di residenza, lavorerò principalmente sulla stesura di una sceneggiatura per un lungometraggio di finzione liberamente ispirato alle “Metamorfosi” d’Ovidio. Il poema, scritto duemila anni fa, concatena più di duecentocinquanta episodi mitologici. Roma presenta un’infinità di rappresentazioni legate a queste narrazioni, che sia attraverso dipinti, sculture, affreschi o architetture.

In che modo l’ambiente dell’Istituto Svizzero influenza la tua ricerca?

La calma di Villa Maraini è un dono molto prezioso per riflettere su numerose questioni, che siano di ordine filosofico o spirituale. In parallelo, lo scambio con altri fellows nonché le numerose attività dell’Istituto sono particolarmente stimolanti sul piano quotidiano.

Qual è l’oggetto più strano che tiene nel tuo spazio di lavoro?

Sicuramente la Rolleiflex, una macchina fotografica a pellicola che suscita sempre una certa curiosità nelle persone vista la sua doppia ottica. Ma, in termini di stranezza, il primato lo ha il mio portafogli a forma di conchiglia che ho comprato in Tailandia.

In che modo l’approccio transdisciplinare arricchisce la tua ricerca?

La cosa più bella è che ci stimola ad adattare costantemente il nostro linguaggio per comunicare la nostra esperienza o pratica rendendoci così più autoriflessivi. Ogni conversazione è un’opportunità per imparare, creare nuove connessioni e relativizzare quei limiti che ogni settore presenta.

Cosa influenza il tuo lavoro?

Se rifletto al mio processo creativo e le opere realizzate sino ad oggi c’è sicuramente una grande varietà di referenze o ispirazioni. Può essere l’esperienza di vita di qualcuno, un documento d’archivio, il titolo di un libro, la forma di una pianta o un gesto di tenerezza che vedo per strada. Non so mai da dove possa arrivare perciò devo cercare di essere ricettivo in ogni situazione, ascoltare bene. In questa eterogeneità il punto di partenza però è la mia identità multiculturale di svizzero e tailandese.

Ha qualche rituale/routine durante il lavoro?

Durante la mattina non accendo il cellulare e cerco di toccare il meno possibile il computer, concentrandomi al massimo sulla lettura e la scrittura a mano. Prima di pranzo colgo l’occasione di svolgere attività fisica in palestra. Nel pomeriggio mi concentro più su questioni di ordine amministrativo, d’archiviazione o ordine generale. Durante il fine settimana cerco di visitare i numerosi musei della città. Per me è davvero importante avere rigore nella routine perché mi permette di prendere correttamente il ritmo che ogni progetto richiede.

Che musica sta ascoltando attualmente?

Ascolto musica durante le sessioni in palestra. Trovo che la musica funky dona un bel ritmo alla corsa. In alternativa alla musica mi piacciono molto i suoni d’ambiente, come può essere una fontana, il passaggio dei pappagalli, delle persone che chiacchierano per strada, un cantiere.

Hai un posto preferito a Roma?

Villa Borghese mi incanta sempre, a partire dall’arrivo, da Via Veneto, in cui bisogna passare sotto le possenti mura aureliane. Poi ci accoglie il verde, i pini marittimi, le statue o il belvedere. Più ci si addentra però e più sembra diventare selvaggio, come se si fosse prossimi ad una foresta.

Qual è la cosa più inaspettata che ti è capitata durante la sua residenza?

Incrociare per caso la pluripremiata regista Jane Champion ai Musei Capitolini è stato sicuramente un momento che mi ha segnato la giornata. Mi aveva particolarmente incuriosito il fatto che stava leggendo un libro e prendeva appunti. Forse preparava il suo prossimo film?

Il futuro per te è… ?

Ho riflettuto molto su come rispondere a questa domanda ma purtroppo, di fronte alla realtà che viviamo, che sia in prima persona, attraverso la stampa o i social media, non è facile articolare un pensiero capace di cogliere in maniera precisa un’idea di futuro. Però mi è tornata in mente la celebre conclusione de “Le città invisbili” di Italo Calvino che, nonostante sia stata scritta nel 1972, resta tutt’ora appropriata e perlomeno “praticabile”

«L’inferno dei viventi non è qualcosa che sarà; se ce n’è uno, è quello che è già qui, l’inferno che abitiamo tutti i giorni, che formiamo stando insieme. Due modi ci sono per non soffrirne. Il primo riesce facile a molti: accettare l’inferno e diventarne parte fino al punto di non vederlo più. Il secondo è rischioso ed esige attenzione e apprendimento continui: cercare e saper riconoscere chi e cosa, in mezzo all’inferno, non è inferno, e farlo durare, e dargli spazio.»