Gianni D’Amato currently works at the Institut Forum suisse des migrations (ISFM), Université de Neuchâtel. He is Professor of Migration and Citizenship Studies, University of Neuchâtel and Director of the nccr – on the move, funded by the SNSF. His research interests include Human Rights, Populism and Contemporary Transformation of Welfare States.

History that fades away? The long farewell of anti-fascism as civil religion

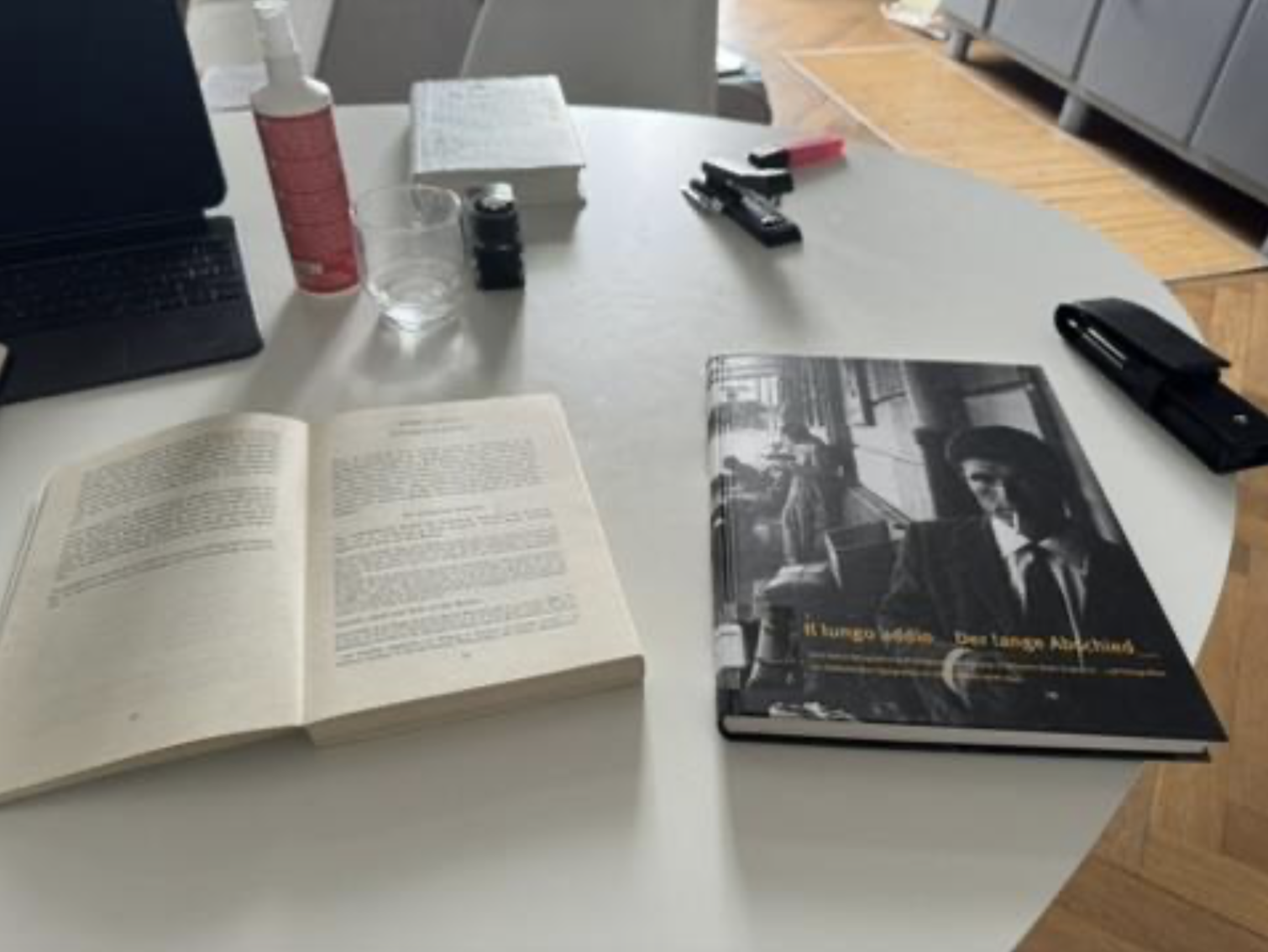

„Il lungo addio“, the final product in the form of a photographic history of the Dieter Bachmann era at Istituto Svizzero in Rome (2000-2003), was dedicated to all Italians who came to work and live in Switzerland. The photo book begins with a picture by Christian Schiefer showing the publicly displayed corpses of dictator Benito Mussolini, his lover Clara Petacci and a companion, who were seized by partisans a few days after the liberation while fleeing north and executed by order of the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale Alta Italia (CLNAI), in which the later President of the Republic Sandro Pertini was also involved.

The end of the fascist dictatorship and liberation from German occupation could only be achieved with the support of the Allied Forces. However, the resistance struggle, in which a non-partisan committee of parties was involved, signaled the break of a generation with the regime as well as the dawn of a new era, even if 20 years of fascism had not left people’s mentalities unaffected and many authoritarian attitudes were passed on. Nevertheless, the Republic was proclaimed (beautifully portrayed in the film „C’è ancora domani“ by Paola Cortellesi) and a constitution was drawn up in the spirit of anti-fascism. Eighty years later and one hundred years after the murder of the socialist member of Parliament Giacomo Matteotti, Italy is governed by a radical right-wing coalition with Giorgia Meloni as the tactically shrewd Prime Minister who wants to secure political power for their parties through an announced electoral reform (for the historical parallel, see Emilio Gentile, Totalitarismo 100: Ritorno alla storia, Salerno Editrice, 2023). Are we observing the long farewell to anti-fascism as Italy’s civil religion? My stay at the ISR is dedicated to examining this question which requires some clarification before the actual research can begin.

Italy as an imagined Nation

The idea that Italy is challenged by a low level of mutual trust is a constant theme in its contemporary reflection (see the Italian debate around Robert Putnam’s book „Making Democracy Work“, Princeton 1994). The literature is legion denouncing a widespread lack of the „moral resources“ of a modern community of citizens, which would require a degree of shared commitment to overarching values to form a cultural community defined by those values. The notion of “many Italies” has been prevalent since the nation’s birth in 1861. Loyalty to family, local community, the church, and formerly political parties — though this has diminished — has traditionally been stronger than loyalty to the nation, shaping Italian social actions over the decades.

Despite their limited strength, the objective presence and effectiveness of national ideas in Italian political culture cannot be denied either. Italian political culture had different conditions for developing a civil religion understood as a “philosophy of the citizen” encompassing moral convictions, political options, social classifications, and perceptions, compared to the U.S., whose civil religion is a paradigmatic example of a democratically understood religious interpretation of national history. In this line of thought, in the process of political self-assertion, the Christian citizen abstracts from himself and adapts to roles within a liberal political system, which relies on preconditions it cannot guarantee itself. The contradictory role of Catholicism and the Church in Italian history — especially during the 19th-century unification process known as the Risorgimento — and in Italian society creates particularly challenging conditions for developing a civil religion. Unlike the U.S., Italy does not have over two hundred years of uninterrupted republican-democratic tradition, although this US-model shows evident signs of erosion. In the 163 years since national unity, Italy has experienced three different forms of government: a monarchy from 1861, a fascist dictatorship from 1922, and a democratic republic only since 1946.

Three historical moments were important in which a civil religion was debated: the Renaissance, the Risorgimento, and the mentioned Resistenza.

For the Renaissance, Nicolò Machiavelli is an important reference who advised Lorenzo de’ Medici, ruler of the Florentine Republic, to unify Italy through cooperation with Milan, Venice, and Naples, while challenging France’s ambitions in Italy. Machiavelli’s writings offer an early example of Italian identity, rooted in the illustrious political myth of ancient Rome. His reflections highlight a critical issue for Italy’s nation-building: the presence of the Papal States. Machiavelli developed a republican tradition critical of the Church, viewing religion’s influence on social integration and political legitimization as a significant obstacle to the unification of Italy.

The Risorgimento (1815-1861) refers to the period in Italian history when political and social movements led to its unification. This period concluded in 1870 with the capture of Rome, marking the completion of Italian unification. In all conceptions of the Italian nation, the reference to ancient Rome plays a central role as a source of a symbol of immortal civilization and the core of national identity. Every high point in national history is seen as a new manifestation of the glorious past.

Italian identity exemplifies the „invention of a nation“ based on a common cultural canon shared by a narrow intellectual elite. However, the initial conditions were particularly unfavorable characterized by large economic disparities, considerable cultural fragmentation, and the absence of a large national bourgeoisie. It became even more harmful during fascism which practiced a divisive totalitarian political religion, based on the glorification of war, of violence and submission. The organization of nationalist symbolism in an organic „national religion“, which had been lacking until then, was probably the real novelty of fascist ideology.

But after two years of a war waged in the wake of the German troops (1941-43), Italy was only able to avoid an early defeat in the Mediterranean with the help of its German ally. The Allied landing in Sicily in the spring of 1943 sealed Italy’s military defeat. During the two years of resistance built up by formerly illegal political organizations from the left to the center against the Republic of Salò and the German occupation, during this civil war that was also a class war and liberation war (Gian Enrico Rusconi, Se cessiamo di essere una nazione, Il Mulino 1993), an anti-fascist civil religion was formed. The cardinal point of this civil religion was the imagination of Italy becoming a constitutional democratic republic and the commemoration of those who shared the values of antifascism and gave their lives for the republican transformation of Italy, which is commemorated in particular on Liberation Day on April 25.

The examination of these rites of commemorations in Parliamentary speeches, from the Cold War to the crises of our days, is the research I will do after my stay at the Istituto Svizzero and during my sabbatical leave in Naples this fall.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Istituto Svizzero in Rome. Any issues or claims arising from the content of this blog contribution should be directed to the author(s) alone.